The Perennial Appeal of Arthur Russell

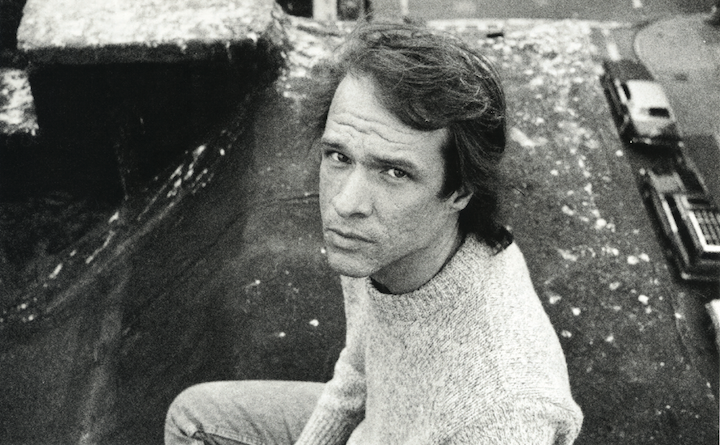

When Arthur Russell died in 1992 at the age of forty, he did so in relative obscurity, having released four commercially unsuccessful albums and granted a single print interview: not exactly a promising oeuvre on which to build a legacy. Yet just over twenty years after Russell’s death, his legacy is in full bloom: a series of posthumous reissues and compilations has amply illustrated his musical virtues; a feature documentary, Wild Combination: a Portrait of Arthur Russell appeared in 2008; a scholarly monograph, Hold on to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973–1992, came out in 2009; and a number of artists have contributed to a series of tribute albums and EPs, the latest of which, Master Mix: Red Hot + Arthur Russell, is scheduled to appear in October of this year. There’s an ongoing shock of delayed recognition at work here: it feels as though Arthur Russell’s time has, finally, arrived. But while his popularity may wax and wane in future, it seems Russell’s time may both never truly arrive nor ever really end.

Russell’s remarkable biography gives us a starting point from which to understand his continued appeal. The son of a former Navy officer, he was born in 1951 in Oskaloosa, Iowa—a small town smack bang in the middle of the North American continent. He moved to San Francisco at the age of eighteen, and lived in a Buddhist commune which forced him to renounce the worldly cello (he continued to practice in a closet). He studied North Indian classical music at the Ali Akbar College of Music, and met Allen Ginsberg, whom he briefly dated and, more importantly, collaborated with on two pieces of avant-garde music, ‘Ballad of the Lights’ and ‘Pacific High Studios Mantras’. Russell soon moved to New York City, nominally to study composition and linguistics, but Ginsberg’s presence may have been a factor. When he arrived in Manhattan in 1973, at the age of twenty-two, he had to borrow electricity from Ginsberg’s nearby apartment via extension cord.

Despite this inauspicious beginning, it was in New York that Russell came into his own as a songwriter and artist. In the great melting-pot of the seventies downtown music scene, he found a wealth of ready collaborators: minimalist composer Philip Glass; David Byrne of Talking Heads; disco pioneer DJs Nicky Siano, Steve D’Acquisto, and Walter Gibbons; and fellow experimentalists Peter Zummo and Peter Gordon. All of these musical scenes were pushed into close contact by physical proximity—avant-garde classical music rubbing shoulders with hedonistic disco DJs, future punk rock stars, and the earliest stirrings of what would come to be called hip hop—and perfectly aligned with Russell’s own creative restlessness. The outcome was a vast library of work, both solo and with an unlikely roster of collaborators (including, believe it or not, a young Vin Diesel, who asked Russell to produce the beats for his abortive attempt at making it as a rapper).

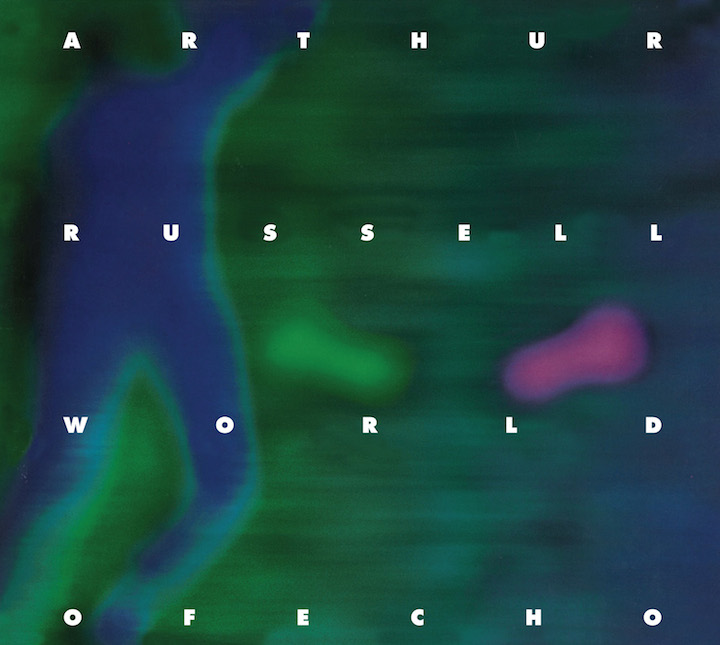

Unfortunately, the same characteristics that made Russell so eminently suited to creating music in this environment meant that very little of his work would ever see release in his lifetime. Russell was both more interested in artistic process than in the product, and a perfectionist: the collision of these two conflicting personality traits means that there are often many versions of any given Arthur Russell track, none of them necessarily the final or definitive cut. His disco projects—dance music tracks made in collaboration with a large number of friends—were often released in small numbers on white label vinyl, then revised and rereleased, then revised again. Even the album that came closest to achieving his unique vision, 1986’s World of Echo, was fundamentally incomplete: Russell planned a companion album which would see the songs performed by brass bands and orchestras in outdoor bandstands to generate natural echo. As his health declined towards the end of the eighties—like so many of his disco collaborators, Russell was both gay and an eventual victim of AIDS—the tussle between his perfectionism and his lack of interest in releasing finalised products resulted in a huge archive of unfinished work, which continues to yield new discoveries to this day.

The creative restlessness that marked Russell’s career stood him in good stead for the internet age. Online, music consumers gleefully hop between genres without a care, and artists mash influences together with little concern for genre purity or authenticity. While it would have been difficult to keep a bead on Russell’s career on the ground in the seventies and eighties—wait, you’re telling me that the guy from Dinosaur who wrote the disco banger ‘Kiss Me Again’ also made two albums of classical music and has been writing country songs on the side in a band called Bright and Early?—the internet’s vast archive allows us to refresh our knowledge of these musical connections with a simple Google search. More to the point, while Russell’s music was informed by certain scenes, it was never entirely of those scenes. His best-known disco song, Loose Joints’ ‘Is It All Over My Face?’, has none of the hallmarks of classic disco—no unctuous bassline, soaring strings, or honeyed vocals—and is instead an exercise in a bracing dancefloor minimalism. Similarly, Russell’s version of country (as showcased on Love Is Overtaking Me) contains flourishes of tabla and hurdy-gurdy, while his interpretation of pop music (as showcased on Calling Out of Context) is rich with dissonant feedback and manipulated cello tones.

More than anything else, though, Russell’s music exemplifies a certain playfulness and curiosity about the sheer sensual joy of being in the world. There’s something very innocent and pure about his work, even when he sings about supposedly adult topics like sex (as he does on, say, ‘Get Around to It’). The cover of Another Thought, the first of his many posthumous compilations, shows Russell wearing a hat fashioned from a newspaper boat, which strikes me as a perfect visual analogy for the childlike sense of exploration that took him from the safe confines of landlocked Oskaloosa, out to the wilder shores of San Francisco and New York City. Although that same sense of exploration would eventually claim Russell’s life, we’re privileged that he left so many of the results of his experiments behind.