David Byrne and St. Vincent’s Love This Giant

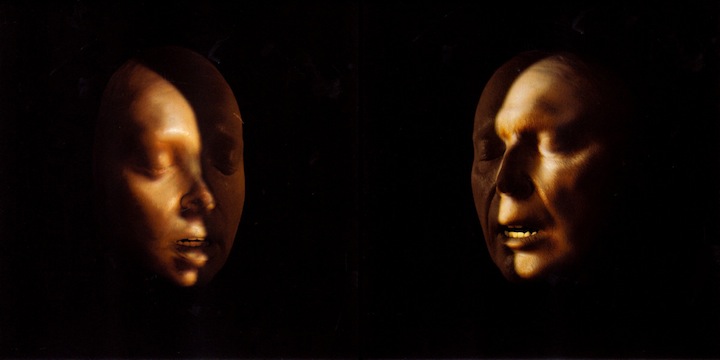

Ignore the prosthetically-enhanced faces on Love This Giant’s cover, if you can—the real visual synecdoche for this album lies inside the gatefold of the vinyl edition. There St. Vincent’s Annie Clark faces Byrne, she on the left and he on the right: each shorn of all hair (including eyebrows), eyes closed, mouths partially open as if singing softly. On the blank canvas of each face the other’s face is projected—thus Clark becomes Clark–Byrne, and Byrne Byrne–Clark.

It’s not only a perfectly creepy and compelling image, but also one that very neatly summarises Love This Giant, almost to the extent that anyone sufficiently familiar with both Byrne and Clark’s respective oeuvres would be able to predict the album’s musical progression by deduction from this image alone. And if there’s a criticism to be ventured of an album as immaculate as Love This Giant, it’s this: it’s an album that’s so perfectly itself, so well-formed and so clearly the product of two towering and idiosyncratic musical talents, that its perfection feels a little stiff and lifeless. Love This Giant may well be impeccable, but it is by no means as loveable as it sounds on paper.

Love This Giant began its life as a small project with modest goals. Byrne, an incorrigible collaborator post-Talking Heads, had previously worked with Clark during the recording of Here Lies Love, the unwieldy concept opera-cum-double-album he co-created with Fatboy Slim. (Quite why one of the late twentieth century’s bona fide musical geniuses would spend so much time working with the man who bequeathed ‘Slash Dot Dash’ to the world remains something of a mystery.) Clark was drafted in to sing as Imelda Marcos on that album’s song ‘Every Drop of Rain’, and she obviously made something of an impression on Byrne. Later the duo were approached by Housing Works, the same charity that commissioned the collaborative concerts between Björk and Dirty Projectors that became Mount Wittenberg Orca, to perform a similar concert. The concert never occurred, but Love This Giant slowly took its current form between Byrne and Clark’s other commitments.

The record’s brass-centred arrangements emerged out of necessity—Housing Works’ concerts are held in a bookstore where space is at a premium, and a brass band wouldn’t require amplification—but the instrumentation serves a dual purpose, without which Love This Giant wouldn’t be possible. Firstly, brass instruments fit neatly within each collaborator’s respective musical idiom: think of the skronky sax licks of St. Vincent’s ‘Marrow’, or the ironic white-man salsa of Talking Heads’ ‘Mr. Jones’. Secondly, the restricted instrumental palette forces the collaboration to focus, and prevents it from veering off into an experimental wilderness.

But if brass arrangements allow the contributors to talk to each another, the glue that cements these arrangements is John Congleton’s characteristically beefy drum programming. Together, these elements create a stage for the songwriters to face each other, exchange ideas, and to create a record that’s both more than the sum of its parts but also very slightly less than “more than the sum of its parts” might imply.

The album’s opening salvo, ‘Who’, announces both the album’s ambitions and its modus operandi. The first notes of the album are a characteristically Byrnian earworm of a tenor sax refrain that establishes the song’s instrumental melody—only for the listener to be disoriented when the downbeat of Congleton’s drum pattern aligns with the upbeat of the sax melody, instantly and uncannily recasting the melody as something profoundly different. Shifting the downbeat to subtly mess with the listener is something of a St. Vincent trope, starting with Marry Me’s ‘Your Lips Are Red’ and carrying through to Strange Mercy’s ‘Chloe in the Afternoon’, and the trope finds its purest expression in the prank of this song’s opening. Similarly, Byrne’s vocals range into territory that he has made his own—the cri de cœur of the perpetually confused American white guy. “Who’s this inside of me?” he wonders aloud in a manner not entirely dissimilar to the famous “My God, what have I done?” of ‘Once in a Lifetime’. In short, ‘Who’ is something like Shiloh Jolie-Pitt, who not only is the offspring of two ridiculously good-looking people but also quite clearly derives her individual features from one parent or the other—Brad’s jaw and eyes, Angelina’s lips and nose.

Many of the record’s other songs, by contrast, have muddier genealogies; it’s harder to tease out the individual contributions of each artist in ‘Weekend in the Dust’ and ‘Dinner for Two’. This makes sense for a collaboration without rigorously defined rules—Byrne and Clark apparently swapped melodies and lyrics back and forth, working on each others’ material until the traces of each component’s genesis were obscured. While this makes for better musical trainspotting among Byrne/Clark devotees, it doesn’t necessarily make for stronger songs: ‘I Am an Ape’, for example, feels slightly unfocused, meandering along despite its crisp structure and short playing time.

Bringing in further contributors could only further dilute this mélange, which explains why ‘The One Who Broke Your Heart’ is, for my money, the weakest song on this album—featuring both the Dap-Kings and Daptone labelmates Antibalas, it comes off as a pastiche of Latin American music cliches. But for each of these relative misfires, there are moments where the collaboration truly sounds like something neither could better in solo mode. Take, for instance, the two songs that anchor the album’s middle, ‘I Should Watch TV’ and ‘Lazarus’. The first is underpinned by a claustrophobia-inducing synth pulse from which flighty, nervous brass lines try valiantly to escape, while Byrne triumphantly howls, “The more I lost myself, the more it set me free!” ‘Lazarus’, by contrast, employs the same effect in reverse: airy, perfectly-spaced horns are dragged down to earth by Clark’s guitar and and Congleton’s meaty beats, while Byrne adopts a rare menacing pose: “You will not see my face come morning,” he warns. “I did not come to set you free.”

While such moments are to be wholeheartedly welcomed, they are comparatively rare on Love This Giant. It is, of course, a very good album from start to finish—but you would expect that from an elder statesman of American alt-pop and one of the brightest talents of the current NPR-approved indie-rock scene. And expectations, it turns out, are what bedevils Love This Giant. A listener familiar with both Byrne and Clark’s work will quite rightly come to it with high expectations, which it will frequently meet and occasionally exceed. But it turns out that Love This Giant can’t quite meet the expectation—an absurd one, I know—that it would transcend our expectations.